General, quoting & support.

Add: Building E, No.58, Nanchang Road, Xixiang , Baoan District Shenzhen City, Guangdong, China

Tel : 0755-27348887

Fax : 0755-27349876

E-mail : svc@pcbastore.com

What is PCB Thickness

Simon / 2021-02-14

Contents [hide]

Almost all measurements have a basic standard from which similar things can be gauged. This is particularly the case with industrial products, household items, and other manmade structures.

Printed Circuit Boards (PCBs) are electronic components, whose standard thickness is in tandem with the design of the finished gadget. By the word "standard", we are considering the industry-accepted figure or size, but not an official statement. This article breaks down the thickness of the board and the various aspects related to the thickness.

What is Standard PCB Thickness?

There is no defined standard PCB thickness, but this is implied in the typical PCB thickness, which is 1.57mm, or 0.062". This figure was adopted as it was the thickness of Bakelite sheets originally used as the substrate in PCBs.

The 0.062" thickness is thus regarded as the standard PCB thickness.

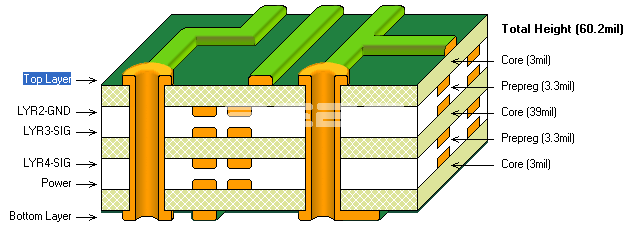

The PCB thickness can further be broken down into the individual thicknesses that constitute the entire board's thickness.

PCB board thickness

This is the thickness of the substrate layer, which is the main structural material, and the insulating layer. Just as mentioned above, 0.065" is the industry's standard thickness, and now the PCB board thickness.

Alongside the standard boards, thinner boards (from 0.008") are mostly produced from epoxy boards which are better than plywood or Bakelite, while multilayered PCBs are usually the thicker (up to 0.0240") ones.

PCB trace thickness

This aspect is usually influenced by the design of the PCB, as per the designer's calculations. The main consideration for the trace thickness is ensuring that it does not overheat, and thus destroy the board.

Basically, when the amount of current flowing through the traces increase, the copper starts to heat up due to electrical resistance. The PCB traces must therefore be sufficiently wide to allow higher amounts of current without overheating.

To arrive at the trace thickness, engineers and designers compare the increment in temperature against the corresponding amount of current. This way, the thickness that can safely allow fluctuations of temperature between the design (average), and the maximum possible temperature is determined. This thickness is the trace thickness.

Current PCB design software has an inbuilt trace width calculator that determines the trace thickness according to the circuitry. Such software recommends the internal traces be broad as well, to accommodate the heat they generate, and that which is conducted from the outer layers.

PCB copper thickness

Copper is the main conductive element in a PCB. Thus, its thickness has to play a rather definite part in the standard thickness of the board. The standard copper thickness is achieved by having one ounce of copper applied over a one-foot square area. A few punches on the calculator and you get 0.00137". This would be commonly termed as 1.37mils.

The internal copper layers are usually between 1.4 mm and 2.8mm, to handle the temperature rise.

The standard copper thickness is thus 1.37 mils but can be increased to handle more current. More copper would mean more money, increasing the overall manufacturing time and cost.

What is PCB Thickness Tolerance?

To ensure that boards fabricated, either in-house or in a factory, work properly in their intended applications, the IPC provides guidelines that set out PCB thickness tolerance. This tolerance refers to the allowable variance in the number of substances used in PCB production. The allowance is usually the difference between the minimum permissible amount and the maximum permissible amount.

How to Specify PCB Thickness

The easiest and most convenient way of specifying PCB thickness is to use a trace width calculator. The calculator requires you to enter parameters such as the solder mask thickness and prepreg thickness. These calculators are very accurate, calculating up to 0.01mm.

Choosing the Thickness of PCB

The standard rule of thumb when choosing a board is to go for a thicker board unless you have to use a thin one. This is because thicker boards are lesser likely to crack as compared to thin ones. Nevertheless, designers often find themselves having to either use standard-thickness boards or customize according to the need. The standard boards are easier to produce and work with, but if the designer chooses to customize, the following factors need to be considered:

1. Contract manufacturer's equipment capability

Before any other thing, you should ensure your manufacture has the equipment necessary to produce a board of your desired thickness. Making this consideration during the design process allows you enough time to locate a manufacturer whose equipment is capable of any advanced designs. You should however understand that this comes at an extra cost.

2. Longer turnaround time

Unlike standard-thickness PCBs which mostly do not call for adjustments during manufacture, customized thickness boards take time to accommodate properly. During manufacture, the equipment settings require numerous changes and adjustments to accommodate a custom thickness. Since these adjustments take long, the manufacturing is highly likely to be delayed. It gets worse if there are special design features to be incorporated.

It's best to discuss these factors with your manufacturer before commencing your project. This allows you to make better estimates of your project's timeline.

3. Additional costs

One major disadvantage of custom thickness boards is the cost and time incurred. Should you opt for custom thickness, ensure that the associated cost and turnaround time are worth the expected benefit. For instance, the changes required to work with a custom-thickness board are rather unforgiving, as compared to the higher cost if special materials were used instead of the standard ones.

4. Impedance

Although the impedance will likely be taken care of in the trace width calculator, you should understand how the custom size affects impedance control. The PCB's thickness is pertinent to the impedance control on that particular board.

Factors That Impact PCB Thickness

Sometimes the standard PCB thickness may not be what a project demands. This is where a custom-thickness board comes into the picture. There are numerous factors, both design and manufacturing, that necessitate the use of a custom board. We look at these factors, finally.

a) Design factors

Design considerations are the primary determinants of whether or not a standard-thickness board will be suitable. These considerations revolve around the board's functionality and application.

i. Copper thickness

Depending on the maximum amount of current expected to pass through the board, the copper thickness may be adjusted. If the current is high, a thicker copper layer must be used. The board thickness increases as the copper thickness increases. The cost will similarly rise to cover the extra copper used, and the complex process of customizing the board thickness.

ii. Board materials

The laminate and substrate layers in a PCB provide the necessary structural support. These parts may be made of different materials such as glass weave, ceramic, and epoxy resin in the substrate. The choice of the material depends on the preferred dielectric constant. On the other hand, laminates may be made of paper layers and a thermoset resin. Laminates and substrates are manufactured depending on the desired properties, which impact the overall board thickness.

iii. Number of PCB layers

The more the layers in a PCB, the thicker it becomes. A standard-thickness board can have up to six layers. Adding any more layers will not be possible if the standard width must be maintained. It is better to use a thicker board than try to fit thinner layers in a standard-thickness board.

iv. Types of signals

Just like with electric current, if a board is expected to transmit high-power signals, the copper needs to be thicker, and the traces wider. Understandably, this calls for a thicker board to accommodate the extra copper.

This is however not the case with high-density boards. These boards typically use performance materials, and thin traces, reducing the board thickness to lesser than standard in some cases.

v. Types of vias

Vias allow traces to be connected between layers of a PCB, through the board. The different types of vias take up different amounts of space, which culminates in the board thickness. For example, micro vias are widely applied in boards that must be manufactured to a smaller thickness.

vi. The environment of operation

Depending on where the board is to be used, it may need to be thicker. For example, if the board is to be subjected to rough handling, it has to be structurally capable of withstanding the handling. A thick board would be more suited for such applications.

b) Manufacturing factors

Manufacturing factors are usually dependent on the CM. The factors may include:

i. Equipment for drill-hole

Drill hole manufacturing is largely dependent on the ratio (aspect ratio) of the depth of the hole to the diameter of the drill hole. When drilling through aboard, the thickness will thus be a limitation at some point. An aspect ratio of 7:1 is quite achievable, but anything higher may not be readily attainable. This is because drilling a small hole through a thicker board is very difficult.

ii. Copper thickness

During manufacture, copper is etched onto the board surface. This etching process is largely impacted by the internal copper layer thickness, which is why etching thicker copper traces has to involve an extra level of manufacturability. The cost and design of the PCB will have to be adjusted to match up the required copper thickness.

iii. Number of layers

The number of layers in a board can only be increased to a certain maximum before the board thickness requires to be increased. Even so, some manufacturers can readily achieve this, while others cannot.

iv. Depenalization method

Manufacturers use the depenalization method to manufacture a large panel containing many individual PCBs which are then cut up to individual PCBs. Whereas thin boards can easily be cut up by drawing breakaway tabs, thicker boards require extra care when depanelizing. Scoring is usually the preferred way of doing the latter.

Conclusion

As we've seen, the standard PCB thickness is not a fixed figure, but a range that may or may not be exceeded. The above factors that impact the PCB thickness are a pointer into how undefined standard PCB thickness is. You must always consult with your CM during both the designing and manufacturing phases. This can help avoid awkward inconveniences brought about by delays and surged costs.

Previous article:Everything About Via in Pad Technology